I have a new paper out!

Gwilym Lockwood, Peter Hagoort, and Mark Dingemanse. “How Iconicity Helps People Learn New Words: Neural Correlates and Individual Differences in Sound-Symbolic Bootstrapping.” Collabra 2, no. 1 (July 6, 2016). doi:10.1525/collabra.42.

The paper can be read and downloaded right here:

http://www.collabra.org/article/10.1525/collabra.42/

…and because we’re doing the whole open thing properly, you can also download the original stimuli, data, and analysis scripts here. You probably have no intention of sifting through it all, but the point is that you can:

https://osf.io/ema3t/

The experiment was pretty similar to my Sound symbolism boosts novel word learning paper from a few months ago, except that this time it was only with the ideophones, and I used EEG to measure participants’ brain activity while they learned them. People learned 19 ideophones with their real Dutch translations and 19 ideophones with their opposite Dutch translations. After I told them about that and said sorry for the deception, they heard all the ideophones again and had to guess what the real translation was from a choice of two antonyms.

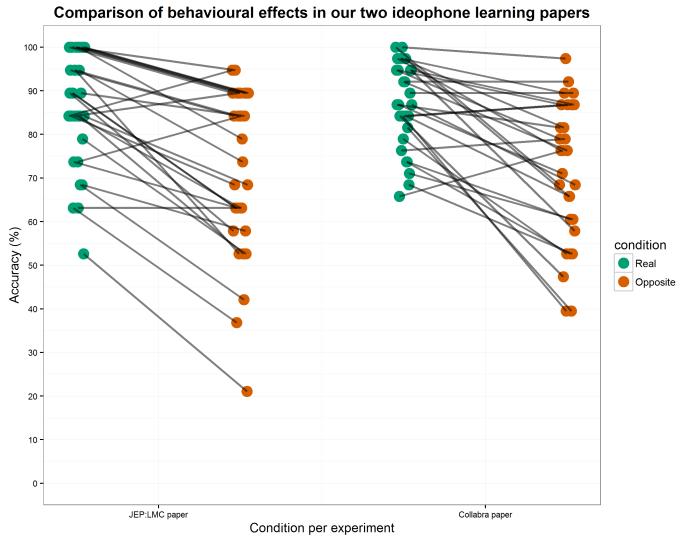

The first important thing is that the results were almost identical. People got the answers right 86.7% of the time for the ideophones in the real condition, and 71.3% of the time for the ideophones in the opposite condition. When they had to guess, they got it right 73% of the time. These figures replicate the first study very closely (86.7% to 86.1%, 71.3% to 71.1%, and 73% to 72.3%), which is excellent news.

All kinds of things can happen in scientific studies, so replicating a study is really important for showing that the effect is real and not just coincidental. Sadly, replications aren’t considered to be very glamorous, so a shocking amount of published science is either unreplicated or unreplicable:

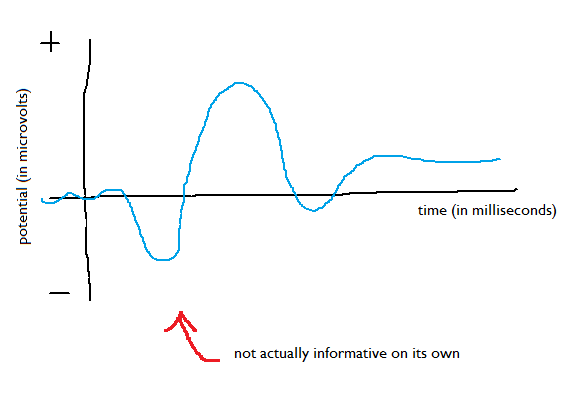

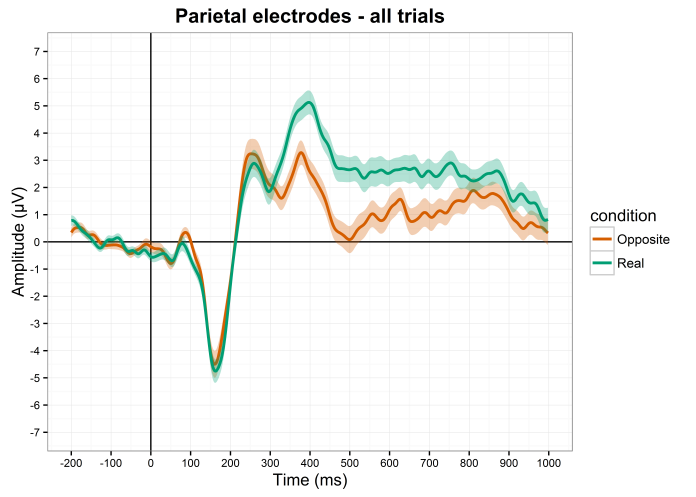

The second part of this new paper is that I also measured people’s brain activity using EEG. Once you average all the trials together, you get a signal of changing activity over time in response to a thing, which is known as an event-related potential. It looks a bit like this, and isn’t that useful by itself:

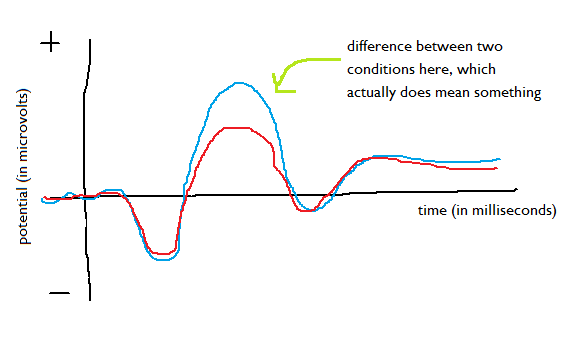

Instead, you have to compare two conditions. If they differ at a certain point, that’s what tells you about how the brain processes things:

In this experiment, I found a big P3 effect in the test round:

The P3 is linked to memory and learning, so it’s not surprising that it came up in a task involving memory and learning. A lower P3 is linked to things being more difficult to learn, so again, it’s not surprising that the ideophones in the opposite condition have a lower P3 when they were harder to learn.

But, it wasn’t that simple. If it was a straight up learning effect, you would expect a correlation between how well people did in a condition and that condition’s P3 amplitude; people with lower test round scores in the opposite condition should have a lower P3 amplitude in the opposite condition. But they don’t.

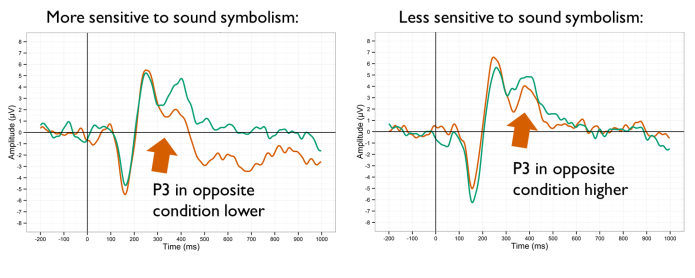

However, there was a correlation between how sensitive participants were to sound symbolism (as measured by their meaning guessing accuracy in the task after the test) and how big the ERP difference between conditions was. When I split the participants into two groups (people scoring above and below the 73% average in the guessing task) and plotted their ERPs separately, it turns out that the P3 effect is big for the people who are more sensitive to sound symbolism and barely there at all for the people who are less sensitive to sound symbolism:

You can also see that the P3 amplitude in the real condition was the same across both groups. What’s behind the difference is how the amplitude in the opposite condition changes. This suggests that most people can recognise cross-modal correspondences and exploit them in word learning, but that some people are more sensitive to sound symbolism and get put off by cross-modal clashes as well.

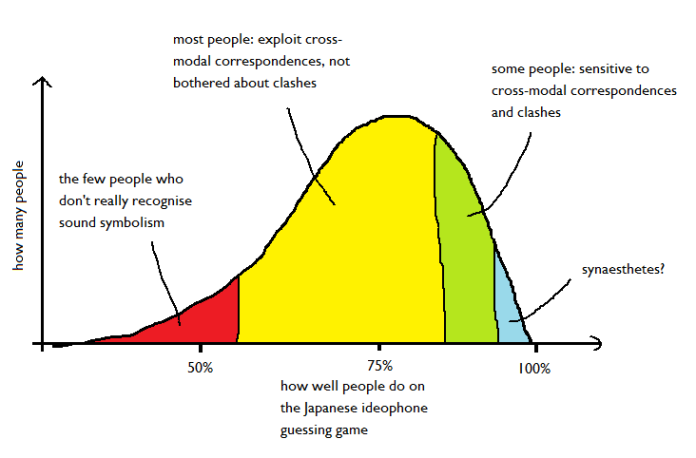

I reckon that the variation in how sensitive people are to sound symbolism goes a little like this:

…and we do have some preliminary data from a massive cross-modal perception and synaesthesia study that shows that synaesthetes are better at the Japanese ideophone guessing game than regular people, but that’s another blog for another time.

Pingback: All the small things: tips and tricks I picked up when revizzing my PhD work - The Data School